The current issue of UHD’s Skyline magazine is dedicated to the memory of UHD professor and acclaimed artist Floyd Newsum. In the magazine’s prelude, Dr. Hayden Bergman writes: “Longtime Art Professor Floyd Newsum said, ‘An artist should not limit themselves

to one medium,’ that they should instead, ‘Dare to do other things.’” And, indeed, Professor Newsum did, as is in full display in “Floyd Newsum: House of Grace,” currently at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, Tennessee. The exhibition features his works created between 2002-2024, ranging from large paintings on paper to maquettes of his public sculptures.

The current issue of UHD’s Skyline magazine is dedicated to the memory of UHD professor and acclaimed artist Floyd Newsum. In the magazine’s prelude, Dr. Hayden Bergman writes: “Longtime Art Professor Floyd Newsum said, ‘An artist should not limit themselves

to one medium,’ that they should instead, ‘Dare to do other things.’” And, indeed, Professor Newsum did, as is in full display in “Floyd Newsum: House of Grace,” currently at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, Tennessee. The exhibition features his works created between 2002-2024, ranging from large paintings on paper to maquettes of his public sculptures.

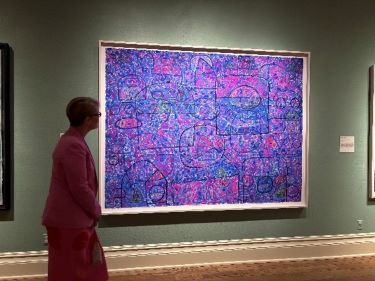

Simply put, Professor Newsum loved color, especially blues that are so intense they mesmerize, drawing the viewer into the painting. Beautifully curated in room after room within the Dixon Gallery, the exhibition is a testament to his love of color with walls that seem to burst with the vibrancy of each piece of art. (That’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences Dean Wendy Burns-Ardolino, Ph.D., taking in “Blue” (2023) at the opening.)

As wonderful as the exhibition is, it is a bittersweet experience. Born and raised in Memphis, Newsum graduated from the Memphis Academy of Art (later Memphis College of Art) and moved to Philadelphia to attend graduate school at Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University. After finishing his MFA in 1975, he and his wife Janice moved to Houston in 1976 for his position with UHD, where he would teach, mentor, and create art for the next 48 years.

“Floyd Newsum: House of Grace” was to act as a reintroduction of his work to his hometown— the first major exhibition of his work in Memphis and a true homecoming. Newsum was finalizing plans for the exhibition when he unexpectedly passed in August 2024. His family courageously decided to go ahead with the exhibition, and they, along with extended family, friends, and Dixon patrons, celebrated his art and the artist at the opening on Saturday, Feb. 8, 2025.

What becomes evident in a survey of his works of this magnitude is that the child-like quality of his compositions belies the sophistication and complexity of his work, work that is extremely personal and symbolic with marks and applied figurines that held great meaning for him—of family, faith, social justice, and community. “His densely layered images include painting in oil and acrylic with collaged photo transparencies and embedded three-dimensional objects including plastic forks, doll-house-sized wooden ladders, and the remnants of artistic materials such as partially used pastels for their paper labels,” writes Ellen Daugherty, Assistant Curator, in the show’s catalog.

The ladder was one of Newsum’s favorite symbols, emblematic of accession, Jacob’s Ladder, his father, and so much more. Floyd Newsum Sr. had been among the first Black firefighters in the South. Engaged in activism during the Civil Rights’ Movement of the 1960s, he would take Floyd Newsum Jr. to rallies and protests, instilling in him a sense of fairness and justice. As UHD Art Professor and Director of the O’Kane Gallery Mark Cervenka explained during his lecture the day following the opening, “The ladder was definitely an iconographic element that could mean rescue, hope, accession. For Floyd, when you hear a siren you know help is on the way. This was a thread in his own life—one who was always there to help.”

Cervenka also shared the influence of the decorative mural paintings by the women of Sirigu, Ghana, on Newsum. The women artists paint large geometric shapes on the outer mud walls of dwellings, storehouses, and compound walls. Eventually, rain and weather erase the art, and the women begin again. Newsum credited this discovery (he never traveled to Sirigu but learned of this practice from a book) with freeing him to paint more abstractly. “These murals really captivated Floyd’s imagination. The idea of ‘preciousness’ was no longer a thing—it was a freeing process, allowing him to create art from his inner being.”

Newsum’s evolution of his work in the last four years alone is something to behold, in some ways a move from pure abstraction to more figurative painting with layers upon layers of symbols for the viewer to discover. “Look to see what is hidden and experience the joy of discovery. That was Floyd’s wish,” said Cervenka. And the greatest joy of “Floyd Newsum: A House of Grace” is to see the incredible output over the last 22 years, with one smallish room with three extremely large canvases of his most recent works, a chapel of sorts perfect for meditating on what Newsum is telling us. (That’s Professor and Arts and Communications Department Chair Azar Rejaie, Ph.D. and Mark Cervenka in front of “Lemon Extraction” (2023).)

“Floyd brought such joy and hope wherever he was. We need more people in the world like Floyd right now,” said Dean Burns-Ardolino. She is right. Although his presence is missed in the hallways and studios at UHD, his spirit was very much felt in the Dixon Gallery that night. And now Memphis is a little brighter and that much more hopeful to have the work of their native son so beautifully on display for all to see. It’s there until April 6 (fingers crossed the exhibition finds its way to Houston), so make a trip to Memphis if you can.